I don't think that anyone involved in the production of the 1986 comedy Short Circuit thought that they were making an important or influential work, but in a very real way, they were. Just as director John Badham's 1983 film War Games inspired real life hackers to create some of the programs invented from whole cloth for the film, Badham's depiction of robotics in Short Circuit (which borders on science fiction) may well have important ramifications for the future of the field.

The film itself is about a robot named Number 5, originally designed as a military weapon. In a freak accident, Number 5 is struck by lightening and gains sentience. He suddenly becomes a living, thinking, feeling being. Number 5 escapes the lab where he was built and embarks on a series of adventures across the Pacific Northwest, pursued all the while by solider (and other robots) who want to destroy him. Here is a clip of the newly alive Number 5 taking on his non-living brethren. The difference is pretty clear.

There is a scene about 2/3 of the way through the film where Number 5 and his creator, Newton Crosby (played by Steve Guttenberg), sit down and have a long tete a tete (sadly, there does not appear to be a YouTube clip of this scene). Crosby refuses to believe that Number 5 has truly gained sentience and insists that though robots may seem very lifelike they ultimately only do and know what they are programmed to do and know.

A mantra he repeats at several points throughout the film is "It's a machine. It doesn't get pissed off, it doesn't get happy, it doesn't get sad, it doesn't laugh at your jokes, it just runs programs." Crosby's objective in the conversation is to prove that Number 5's wise-cracking, sass-mouthing, and aversion to being "disassembled" is merely the result of an elaborate malfunction (essentially a reprogramming) that is sending Number 5 new and confusing signals. To that end, he subjects Number 5 to a series of tests and questions that prove inconclusive. What ultimately convinces Crosby that Number 5 is, in fact, alive is a joke. A non-sentient machine, even a sophisticated pop culture spouting one, would have no response to humor. You can't program a robot to know what is funny because no one can say empirically what is funny. It's a completely involuntarily and subjective response that would be impossible to program into a machine.

A mantra he repeats at several points throughout the film is "It's a machine. It doesn't get pissed off, it doesn't get happy, it doesn't get sad, it doesn't laugh at your jokes, it just runs programs." Crosby's objective in the conversation is to prove that Number 5's wise-cracking, sass-mouthing, and aversion to being "disassembled" is merely the result of an elaborate malfunction (essentially a reprogramming) that is sending Number 5 new and confusing signals. To that end, he subjects Number 5 to a series of tests and questions that prove inconclusive. What ultimately convinces Crosby that Number 5 is, in fact, alive is a joke. A non-sentient machine, even a sophisticated pop culture spouting one, would have no response to humor. You can't program a robot to know what is funny because no one can say empirically what is funny. It's a completely involuntarily and subjective response that would be impossible to program into a machine. The joke that Crosby tells Number 5 goes like this:

"There's a priest, a minister and a rabbi. They're out playing golf. They're deciding how much to give to charity. The priest says 'We'll draw a circle on the ground, throw the money in the air and whatever lands inside the circle we'll give to charity.' The minister says 'No, we'll draw a circle on the ground, throw the money in the air and whatever lands outside of the circle, that's what we'll give to charity.' The rabbi says 'No no no . We'll throw the money way up in the air and whatever god wants, he keeps!'"

Number 5 five finds this joke to be hysterical and laughs uproariously, thus proving that he is not just running a program, but is actually a sentient, living thing. The world's first inorganic life form. What's both troubling and fascinating about this scene is that the joke Number 5 finds so funny is kind of anti-Semitic. In order to "get" the joke one must be aware of certain negative stereotypes about Jews. Clearly Number 5 is not only aware of them, but amused by them. What's interesting about this is that in the image of a robot laughing at an anti-Semitic joke, we are given a glimpse of what will quite possibly be the future of robotics. Though Short Circuit itself is largely preoccupied with the issues if of machine intelligence that have been the focus of programmers and robotics engineers for decades, the film inadvertently offers a brief look past those 20th century issues and into the issues that will be facing the scientists working with artificially intelligent machines in the 21st century.

For years the central question among computer scientists has been "can machines think?" In the early 1950s a man named Alan Turing (widely reguarded as the father of modern robotics) proposed that this could be determined via a test, now famously known as the Turing Test.

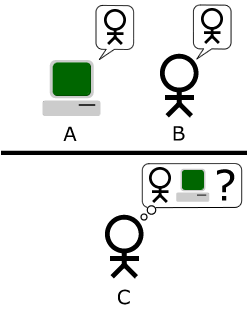

The basic idea of the test was that a human subject (C) would engage in a conversation with two other subjects, one a computer (A), the other also human (B). The conversation would be conducted via a text based medium with all three subjects in separate rooms. Turing proposed using teletype machines (a forerunner of the modern fax machine), but essentially what he was looking for was our modern instant messaging technology. If subject C could not distinguish between the computer and the other human in the conversations, the machine would be deemed intelligent as intelligence is a prerequisite for true conversation.

The basic idea of the test was that a human subject (C) would engage in a conversation with two other subjects, one a computer (A), the other also human (B). The conversation would be conducted via a text based medium with all three subjects in separate rooms. Turing proposed using teletype machines (a forerunner of the modern fax machine), but essentially what he was looking for was our modern instant messaging technology. If subject C could not distinguish between the computer and the other human in the conversations, the machine would be deemed intelligent as intelligence is a prerequisite for true conversation.The flaw in the Turing Test is that it is difficult to determine whether a machine is engaging in actual conversation or merely running a sophisticated program that convincingly mimics conversation. This is exactly the dilemma Crosby faces in the discussed scene in Short Circuit. What we as audience members know, however, is that, since Number 5 is alive, Crosby's questions are a waste of time and Crosby himself is one step behind the curve. The questions Crosby is asking have already been answered. Without realizing it, however, Crosby, and the filmmakers behind Short Circuit, stumble onto what will inevitably be the central question of the next generation.

When we live in a world where the intelligence of machines is presumed (as we inevitably will), the Turing Test becomes obsolete. A new test will be needed to answer a new set of questions, but what will those questions be? It would seem that the obvious follow up to "can machines think?" is "what do machines think?" When machines no longer only know what we tell them, it becomes of the utmost importance to figure out what conclusions they have drawn on their own. Short Circuit provides us with one possible test, which can easily be described as "The Guttenberg Test."

The Guttenberg Test is simple: Intelligence having been established, a machine is told a racist joke. If the machine laughs, then that machine is a fucking asshole. Congratulations, Nova Robotics, you built a racist dick-bot. The Nobel Committee will be along presently.

Scientists could easily develop numerous variations on The Guttenberg Test. One possibility would be the "Dullea Test," in which two or more humans quietly gossip about a machine behind its back in order to answer the question "can machines take it personally?"

And, of course, there would be the "Spiner Test," in which a robot is given a series of instructions coded in common human idioms to answer the question "can machines provide hackneyed comic relief?"

1 comment:

I can't believe how far into this post I had to read before you came to your real point. And when you did, I felt like I was sucker punched with hilarity. Seriously.

Post a Comment